International Art Theft and the Recovery of Stolen Art

O ne summertime morning in 2008, Christopher Marinello was waiting on 72nd Street in Manhattan, New York. The traffic was decorated, but after a few minutes he saw what he was waiting for: a gold Mercedes with blacked-out windows drew near. Every bit it pulled upwards to the kerb, a man in the passenger seat held a large bin-liner out of the window. "Here y'all go," he said. Marinello took the pocketbook and the automobile sped off. Within was a rolled-upwardly painting past the Belgian artist Paul Delvaux, Le Rendez-vous d'Ephèse. Its estimated worth was $6m, and at that indicate it had been missing for 40 years.

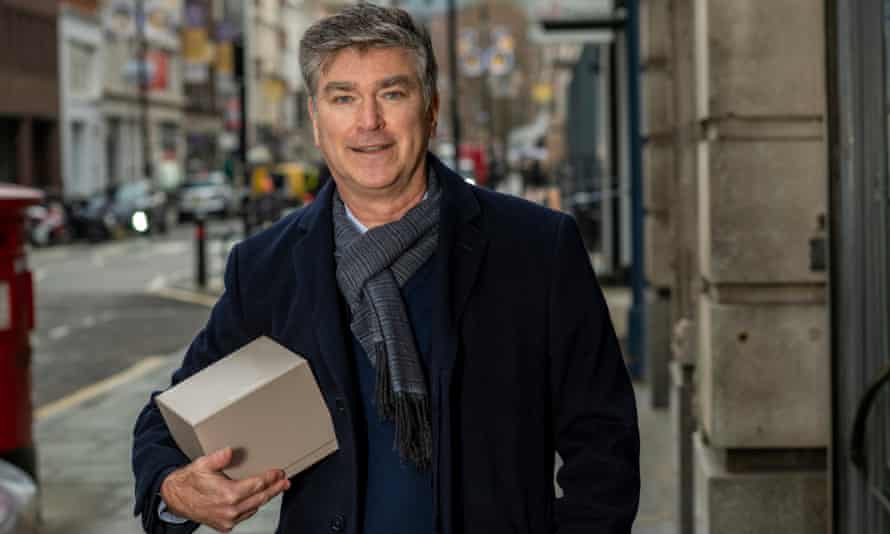

Marinello is one of a handful of people who rail down stolen masterpieces for a living. Operating in the grayness expanse betwixt wealthy collectors, private investigators, and loftier-value thieves, he has spent three decades going afterward lost works past the likes of Warhol, Picasso and Van Gogh. In that time, he says he has recovered art worth more than half a billion dollars. When I telephone call him, he answers, and so abruptly hangs up. "I was just on my mode to a constabulary station to recover a stolen sculpture," he explains later, apologising.

Cases tend to go the following style. A stolen artwork – in this instance, a bird by the Martin Brothers pottery makers, which was swiped from a London library in 2005 – will often turn up at auction or on social media. It then falls to Marinello to constitute whether it is actually the missing work and, sometimes, to get information technology back. This, he says, is usually relatively simple.

Stolen works often change easily several times before resurfacing, leaving subsequent possessors in the nighttime well-nigh their provenance. This is nigh likely what happened with the Delvaux. The painting, completed in 1967, depicts several nude women in a dreamlike landscape that'southward function classical architecture, part mid-century tram station. Delvaux himself sold it a twelvemonth later, but information technology was stolen before it reached the buyer. In 2008, Marinello got a telephone call from somebody who wanted to return it. What happened to it in the intervening xl years is unclear, although its final location is known. It was rolled upwardly, says Marinello, in the wardrobe of "a very well-heeled celebrity. And their very expensive lawyer made it clear they would never be named."

The pick-upwardly, a meticulously planned functioning, was "one of the more unusual ones". But in Marinello's line of piece of work, information technology pays to expect the unexpected. "I go a huge amount of tips, unremarkably on WhatsApp," he says. "Sometimes they are from informants I work with, but I have to sift through a lot of garbage. I once had a guy tell me the original Mona Lisa in the Louvre was a fake, and that he had the documentation to prove it. That goes in the crazy file."

A slight, 58-yr-sometime Italian American with a soft Brooklyn accent, Marinello went to art school before realising he "wasn't very good". He so trained every bit a lawyer, cutting his teeth as a litigator in New York representing galleries, collectors and dealers in cases involving disputed works. "Eventually, information technology developed into a full-time art recovery practise," he says. In 2013, he formed his own company, Art Recovery International, which is based in Venice but has offices in London.

A former client, quoted on his website, describes him every bit "a mixture of detective, terrier and pin-sharp lawyer", only in conversation, Marinello is polite and yielding. It is hard to imagine him stepping in as an intermediary between the police and owners of stolen art. "I am an attorney, non a badass," he says. "Just I'm a pretty good negotiator. I tin can convince people to do the correct affair."

One such occasion occurred in 2010, when he was approached past a gallery in Toronto. Somebody had offered them an $lxxx,000 bronze sculpture past Henry Moore that had been stolen nine years earlier. When Marinello contacted the seller, the person revealed himself to be a member of the Italian mafia in Toronto. "He made reference to the fact that I am also an Italian citizen," says Marinello, "and that I was giving him a hard time. He said they could do the same to me."

Unfazed, Marinello was able to negotiate the sculpture'south release. "The bottom line," he says, "is that if you are trying to sell something that is stolen, yous're the i with a problem, not me." The mobster, he adds, "could have been arrested for trafficking, for possession, or whatsoever number of things. He needed me more than than I needed him. That was what I had to convince him."

When pressed on how he did this, Marinello sounds awkward. "I can't always say what my methods are." What he will say is that he will never pay a ransom. "Everything I do is legal, ethical and responsible. I'thousand non going to jeopardise my licence [as a lawyer]," he adds. "If I paid off a thief to get something back, they would only come dorsum for more."

He adds: "With a lot of art law-breaking, there is nobody to abort and people rarely get to prison. It's only a matter of recovering the work." However, sometimes a suspect volition turn down to cooperate. Then, things are different. "We go later them similar pitbulls and never allow go," he says. "And that is when they start getting nasty, when they are concerned they're going to go to prison." He says he has received directly threats from people he is pursuing, while his elderly relatives have been intimidated.

As a precaution, Marinello has stopped publishing his address. "God prevent your life is in danger and you do take to deed apace," he says. "There are some very wealthy people in the art earth and they volition absolutely become subsequently you. And as for the criminals, in that location are plenty yous just do not desire to deal with." He lowers his vox. "They'll intermission your legs."

Despite this, he is keen to dispel whatever misconceptions that his work is glamorous. "I guess the movies always make information technology seem that fashion," he says. "But there is a lot of insurance paperwork involved. I spend most of my time earthworks through one-time records and fighting with people over the telephone."

Moreover, art thieves also unremarkably fail to live upwardly to the hype. When Maurizio Cattelan's £4.8m gilded toilet, called America, went missing from Blenheim Palace, Oxford, in 2019, the artist himself praised the perpetrators as "great performers". Marinello takes a dimmer view. "They almost certainly did not steal information technology for its art value. They stole information technology for its metallic value. That leads me to believe it was simply common thugs who knew enough virtually plumbing to remove it."

He continues: "The dumbest thing I ever did was in Amsterdam. I was meeting a former art thief about a $100m Picasso. He was very active in the 70s in the The states, and in prison house was partnered with a big-time drug dealer who knew where information technology was. We were trying to negotiate its return." The coming together was in 2014, around Thanksgiving. "So like an idiot, I took my family with me, including my mother-in-law, and decided to make a weekend of it."

Marinello told the ex-con to meet him at the hotel where he was staying with his mother-in-law in the room next door. "The day we were supposed to meet, she came down to breakfast and said, 'Some guy named Henry called – he wants to see you.' Turns out this guy had chosen the hotel and got my mother in law'south room number. Oh God, I had my head in my easily. I decided never again to mix business with pleasure."

As for the Delvaux? Marinello walked it downward a crowded 72nd Street to a nearby restoration specialist, rolled up "similar a bazooka" in the bin-liner over his shoulder. When he took it out of the pocketbook, the restorer gasped. The painting had been damaged and would eventually fetch simply $1m at auction, $5m less than its original estimated worth. "They'd rolled it upwardly the incorrect way," says Marinello. "The pigment had all flicked off the nudes. Idiots!"

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/may/05/pitbulls-art-detective-christopher-marinello-mobsters-stolen-picassos-lost-matisses

0 Response to "International Art Theft and the Recovery of Stolen Art"

Post a Comment